Whilst researching her book The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk, author Jennifer Niven encountered information about Ada Blackjack, the lone survivor of an arctic venture in the early 1920s. A wealth of documentary evidence in the form of diaries, letters, articles and books aided Jennifer Niven in piecing together this utterly compelling narrative and the story of the ill-fated Wrangel Island expedition became the subject of her second book Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson was a charismatic explorer with a belief in what he called "The Friendly Arctic". He believed that the arctic was not the harsh, dangerous environment it was reputed to be, but with minimal equipment could be a perfectly safe, hospitable home. He had his eye on an island in the Arctic Ocean and was determined to claim rights for future commercial ventures (an airstrip, caribou farming) regardless of the internationally accepted Soviet claim on the land.

As the first phase of this goal, Stefansson hired four young men to colonise the island off the Siberian coast for a year. They were given supplies to sustain them, which they would need to supplement through hunting and trapping, until a relief ship would arrive the following summer. They were advised to hire a few families of Eskimos to aid with the hunting and cooking, but in the end, all the native Alaskans except Ada Blackjack backed out at the last moment. Stefansson himself left all the planning and preparation for the expedition to the four young men, two of whom had never actually been to the arctic before.

Ada Blackjack was a young seamstress working in Nome, Alaska when she was ofered a job sewing and cooking for an expedition on Wrangel Island. With an ill son who needed medical treatment for tuberculosis, the offered salary of fifty dollars a month for a whole year was too much for her to refuse. Without any experience living off the land, Ada was given the tasks of cooking and sewing for the four male explorers who were filled with a sense of excitement and enthusiasm.

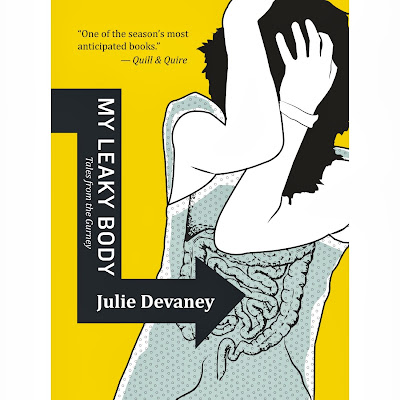

|

| Ada Blackjack, centre, with the expedition members. |

Ill-prepared and inexperienced, Jennifer Niven documents the events from the time they were left on Wrangel Island in late summer 1921 until a relief ship finally arrives almost twenty-four months later to find Ada Blackjack living alone, having taught herself to trap, shoot a gun, hunt seals and chop wood. A story of heart-breaking loss, racism, greed, and exploitation, Ada Blackjack's life was forever changed by her experiences on Wrangel Island. Vilhjalmur Stefannson is exposed as a self-serving charlatan whose instinct for self-preservation trumped everything. The responsibility for the disaster is placed solely at his feet by the author, and she supports this conclusion with a weight of countless documents (the most damning written by Stefansson himself). Jennifer Niven has drawn the personalities of each of the characters out from these documents. Each comes alive in this skillful narrative, none more so than Ada herslef, notwithstanding her reticence to discuss the events of the almost 24 months she spent in the arctic.

|

| Jennifer Niven |

Ada Blackjack's story is incredibly inspirational. She rejected the classification of heroine that many were eager to bestow upon her after her return from the arctic. Using her limited resources, Ada Blackjack was able to motivate herself enough to persevere through fear, isolation, starvation and utter solitude. She took on the responsibility that was thrust upon her by circumstance and rose to the challenge by taking control of what she could. She fought against her overwhelming fear of polar bears and guns and she taught herself to hunt and trap. She built a platform from which she could search for the rescue ship. She was filled with gratitude for being alive and expressed it in her journal entries daily. She found within herself the drive to struggle on, to perform the necessary tasks in the moment, and to look toward her return home so she could provide service for her young son. This was a wonderful story of courage and resilience.